Top 3 Strategies for Improving Social Interactions for Autistic Children

Many autistic individuals struggle with developing appropriate perspective-taking, self-awareness, and self-monitoring skills. They may also have difficulty modifying false beliefs about themselves and others. As a result, interventions supporting these areas can provide meaningful benefits for neurodiverse children in the context of social interactions.

Three specific approaches for improving social awareness, perspective-taking, and self-confidence skills among autistic individuals include:

- Behavior rating scales: to support self-awareness and self-monitoring skills

- Social narratives: to support appropriate perspective-taking skills

- Test of evidence (TOE) strategies: to focus on modifying false beliefs about oneself and others

When implemented efficiently and effectively, these three strategies can help autistic children improve their social anxiety, self-awareness, and relational skills.

Creating Personalized Goals to Improve Social Interactions

Establishing goals for individualized success at the outset of treatment is an important first step in the intervention process. Social skills should be a primary focus as measurable, attainable, and developmentally appropriate goals are set for each child.

Common skills that target and combat social anxiety among autistic children include:1

- Interacting with peers

- Engaging in group conversations

- Collaborating with others

- Identifying preemptive signs of mounting frustration

- Developing adaptive communication and conflict resolution skills

- Encouraging self-advocacy, turn-taking, and parallel play (i.e., playing alongside others)

- Sharing, compromising with peers, imitating (i.e., copying) skills, and providing eye contact

- Joint attention (i.e., sharing the same focus on a physical stimulus or object as someone else)2

- Executive functioning skills (i.e., organizing, planning, inhibition, and attention skills)

- Imaginary play and self-discovery skills

Each of these traits, goals, and skills can help neurodiverse children acquire more successful and appropriate strategies for engaging in social interactions with others while also reducing social anxiety in the meantime. To assist children in developing these skills, behavior rating scales, social narratives, and test of evidence (TOE) interventions are effective methods for treatment.

1. Behavior Rating Scales for Self-Awareness Skills

Behavior rating scales are a common approach for teaching self-awareness skills to autistic individuals. These scales may include one or more of the following as a way to teach children to identify, label, and predict their emotions more accurately:

- Graphs with small, medium, and large figures

- Numbers that range from 1 to 5 or 1 to 10, depending on the child

- Colors such as blue for calm, red for upset, and green for sensory seeking

- Faces varying between very happy to flat and slightly annoyed to very angry

Systematic instruction should focus on teaching children how to rate their emotions throughout the day using a graphical or pictorial behavior rating scale.3 Such an approach allows children to become more aware of how they are feeling in the moment (before situations get out of control and escalate into social withdrawal or problem behavior).

In the beginning, instruction with the behavior rating scale should focus on teaching children to properly identify their thoughts, feelings, and actions throughout the day. Then, intervention should shift to labeling emotions in the midst of difficult situations--prior to withdrawing or engaging in problem behavior. Once the child is able to successfully rate and identify their emotions, strategies for stress management may be incorporated to encourage the child to remain present during challenging situations, refrain from social isolation, and avoid acting out. Autistic individuals should also be encouraged to recognize their emotions in a variety of different settings, environments, and contexts.

Generalization of this skill takes place when the child is taught to use their rating scale in different locations (e.g., at school, at home, when going to a restaurant or park, etc.) throughout the day in order to pinpoint various emotions as they arise. Eventually, the physical rating scale may be withdrawn (i.e., systematically faded out) when the child is able to use self-monitoring strategies independently.

2. Social Narratives for Perspective-Taking Skills

Perspective-taking skills are frequently taught using social narratives (i.e., special stories developed to help a child better understand the thoughts, feelings, and actions of others). These narratives enhance a child’s ability to predict the intentions of others while also helping them gain a greater awareness of the interests of others their age.

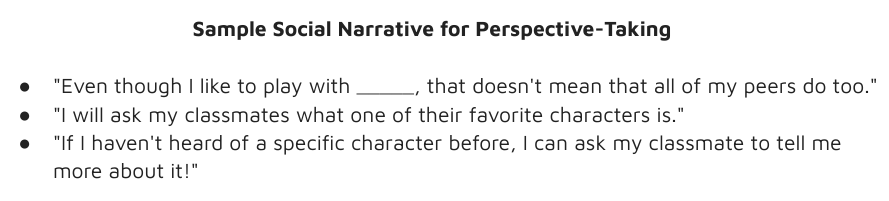

Statements such as these may be included in social narratives to help teach perspective-taking skills:

- “Even though James likes to play with his favorite superhero figurines, that doesn’t mean that all of his classmates do too.”

- “Therefore, James can ask his classmates what their favorite characters are!”

- “James learned that Thomas’s favorite character is Spiderman.”

- “Even though James isn’t very familiar with Spiderman, he can ask Thomas to tell him more!”

- “Sometimes other classmates don’t like the same characters that James likes.”

- “But that’s okay because everyone is unique! James can ask Thomas to tell him about the character(s) he likes--and then James can tell Thomas about his favorite superhero!”

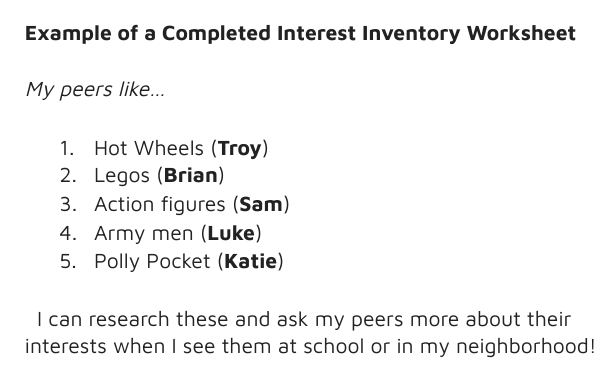

After reading through a social narrative, learners can be provided with an interest inventory worksheet to allow them to make a list of characters for further research.3 In the example above, James could note “Spiderman” on his list as a reminder to learn more about that character after school or the next time he goes to the library. Developmentally appropriate support should be provided by knowledgeable caregivers, educators, or therapists as the child begins researching different topics of interest that their peers have.

The primary goals of social narratives and interest inventory worksheets are to:

The primary goals of social narratives and interest inventory worksheets are to:

- Teach children perspective-taking skills

- Encourage learners to discover new interests, ideas, and/or characters

- Support classmates in including learners on the autism spectrum in school-wide activities (based on their unique interests)

- Give neurodiverse children the opportunity to use the information they learn to build new friendships and initiate conversations with peers

- Receive training on how to be a good friend who considers the likes and dislikes of others

Interest inventory worksheets and social narratives give children on the autism spectrum an opportunity to become active investigators (i.e., individuals on the quest for discovering new characters that their peers find interesting and enjoy talking about). These skills may be implemented as school-wide interventions to encourage all students to participate in learning more about the different characters, superheroes, and/or TV shows that their peers like.4 Teachers should regularly encourage students to research the characters they record on their interest inventory worksheets and provide positive feedback to learners who initiate conversations with classmates about the new information they learn.

Heather Dorn, MS BSBA, has created a series of Social Narratives for STAGES® Learning. You can get them all here!

3. Test of Evidence Strategies for Modifying False Beliefs

A third intervention for assisting autistic children is the test of evidence (TOE) strategy which modifies false beliefs and improves social interactions. This cognitive-behavioral approach highlights the importance of building a child’s self-esteem by encouraging the development (and maintenance) of reciprocal friendships with peers.

Test of evidence (TOE) interventions aid those with autism in recognizing and processing faulty personal beliefs that lead to feelings of low self-esteem. Because some neurodiverse children make sweeping over-generalizations and incorrect conclusions based on faulty assumptions about themselves and others, TOE strategies can help combat and prevent negative thought patterns from forming, taking hold, and affecting a child’s self-esteem in the long run.

TOE approaches typically begin by helping children analyze the logic and assumptions behind the beliefs they hold about themselves and others.3 Children specifically are taught to:

- Generate evidence that disproves the incorrect conclusions and faulty beliefs they have established.

- Consider alternative beliefs about themselves and others.

- Draw conclusions based on the confirming and disconfirming evidence of their current thought patterns.

- Develop new thought patterns that are either neutral or positive (i.e., not negative).

A child who believes that “nobody wants to be their friend”--for example--can be walked through the four steps outlined above with the guidance of a supportive caregiver, teacher, or therapist. The primary goal should be to demonstrate to the child that the faulty thought patterns they have established are not true. This can be accomplished by encouraging the child to look for disconfirming evidence about their current belief(s) and helping the child see that negative self-talk does not serve them well.

A child who believes that “nobody wants to be their friend”--for example--can be walked through the four steps outlined above with the guidance of a supportive caregiver, teacher, or therapist. The primary goal should be to demonstrate to the child that the faulty thought patterns they have established are not true. This can be accomplished by encouraging the child to look for disconfirming evidence about their current belief(s) and helping the child see that negative self-talk does not serve them well.

In the end, the child will, ideally, come to accept a neutral statement like this: “Even though everyone in my class might not be a close friend, I can still talk to several classmates and get to know them better.” A statement similar to the one above can replace negative beliefs that the child previously held--improving their self-confidence, self-esteem, and future friendships with peers in the process.

School-wide Instruction and Peer-Mediated Interventions

School-wide instruction and peer-mediated interventions (PMIs) may be implemented to support a more accepting and understanding environment for all children, regardless of their learning styles, personal abilities, or level of development. School-wide interventions seek to establish consistency for all students by promoting predictable, positive, and safe environments across all school settings. This approach supports improved “social, emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes for all students” while remaining flexible and sensitive enough to meet the diverse needs of all families, students, and communities involved.4 Relatedly, peer-mediated strategies facilitate intentional social interactions between autistic children and their typically developing peers by training peer mentors to initiate conversations, respond promptly, and foster positive interactions among autistic individuals.3

In Summary

Each of the interventions outlined above seeks to help neurodiverse learners develop appropriate perspective-taking, self-awareness, and self-monitoring skills with the end goal of improving their interactions with others and reducing any underlying social anxiety.

Behavior rating scales are an effective approach for teaching self-awareness and emotional regulation skills. Similarly, social narratives and interest inventory worksheets can be used to assist autistic children in the development of perspective-taking skills, and test of evidence (TOE) strategies encourage learners to replace faulty beliefs about themselves and others with neutral statements. Positive relationships with peers can be built and maintained using TOE strategies that foster improved self-confidence and self-esteem.

Importantly, age-appropriate goals should be established for each child at the onset of treatment (before any new strategies are implemented), and progress can be tracked during the intervention stage using graphs and charts to collect, display, and analyze data and trends over time. With appropriate support, autistic children can learn to improve their social interactions and develop stronger perspective-taking, self-awareness, and self-monitoring skills.

References

- https://adayinourshoes.com/social-skills-iep-goals/

- https://autism.unc.edu/resources/autism-definition-and-signs

- Bellini, Scott. Building Social Relationships 2: A Systematic Approach to Teaching Social Interaction Skills to Children and Adolescents on the Autism Spectrum. Overland Park: AAPC, 2016.

- https://www.pbis.org/topics/school-wide

Kenna McEvoy

Kenna has a background working with children on the autism spectrum and enjoys supporting, encouraging, and motivating others to reach their full potential. She holds a bachelor's degree with graduate-level coursework in applied behavior analysis and autism spectrum disorders. During her experience as a direct therapist for children on the autism spectrum, she developed a passion for advocating for the health and well-being of those she serves in the areas of behavior change, parenting, education, and medical/mental health.