Teaching Tools for Making Friends and Developing Online Relationships for Autistic Individuals

Learning social media skills and dating etiquette can be especially challenging for young autistic adults. This article provides tools for helping to learn new digital social skills for autistic individuals.

Friendship and dating involve incredibly complex sequences and understanding subtle cues—both verbal and non-verbal—to determine if both parties want to develop a relationship. From infancy, we constantly take in cues from our caregivers and home situation to pick up on the complexities associated with friendship, intimacy, and affection.

The nature of autism makes it challenging to pick up on social cues, which can lead to maladaptive strategies to gain friendships or a partner. To make matters worse, navigating this complexity through digital platforms like phone text or various apps adds another layer to this Rubik’s Cube we call human interaction. Unfortunately, missteps in navigating remote interactions through a screen can lead to frustration or even more serious consequences.

The nature of autism makes it challenging to pick up on social cues, which can lead to maladaptive strategies to gain friendships or a partner. To make matters worse, navigating this complexity through digital platforms like phone text or various apps adds another layer to this Rubik’s Cube we call human interaction. Unfortunately, missteps in navigating remote interactions through a screen can lead to frustration or even more serious consequences.

Here are some instructional tools to help your autistic loved one or student learn the boundaries and social etiquette associated with interacting through digital or social media.

1. Rating Scales

Social interactions are cloaked in shades of gray: How can I show I’m interested without coming on too strong? How can I tell if someone wants to be friends or doesn’t like me? Rating scales can add a bit of structure to social interactions by giving some parameters from just right to creepy to illegal.

One resource I’ve found really powerful over the years is the book, A Five Is Against the Law. The main concept is a rating scale to help autistic students recognize that the intensity of their interactions can have ramifications for their relationships and even legally. Here’s one scale I’ve used to help an autistic student understand how much texting is okay.

|

Acceptable |

1. It’s been an hour or more since I saw this person so I send them a text and wait for them to respond. |

|

Acceptable, but not advised |

2. It’s been less than an hour since I saw this person and I text them and wait for them to respond. |

|

Borderline Creepy |

3. I send this person multiple texts throughout the day, some without a response. |

|

Very Creepy |

4. I send this person multiple texts within a 3-hour timeframe, most without a response. |

|

Illegal/Harassment |

5. I send this person more than 20 texts in a day, none with responses. |

|

When texting, if the person doesn’t respond. Wait and follow up with them in person. Do not keep texting. |

|

Pairing a rating scale to a specific behavior can help make a gray area more clear-cut and allow for deeper reflection and understanding of social interactions. This type of model can be individualized and modified to reflect interactions through screens or IRL (in real life).

2. Consequence Mapping

Similar to a rating scale, the purpose of consequence mapping is to spell things out: If this happens, then this may happen. Understanding cause-effect relationships can be a challenge for autistic students, so pairing this type of intervention with a visual or even color-coded graphic can help break down situations.

Here’s what this could look like:

- When I sent this friend a Snap, they did not respond.

- If I send another Snap, they probably won’t respond again, may feel uncomfortable, and think I’m annoying.

- If I wait until they send me a message or Snap, then I will know that they want to talk with me and I can respond.

If I were to put a visual with this, I would have a green sequence indicating positive choices and outcomes for the situation and another pathway marked in red indicating negative choices and outcomes.

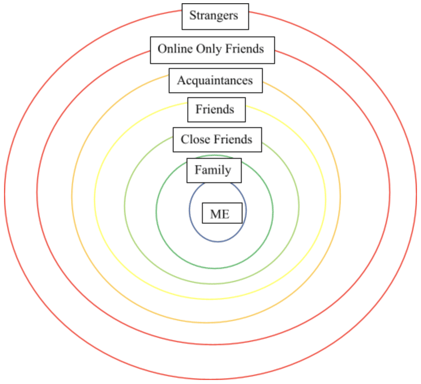

3. Visual Supports - Circle of Friends

Sometimes understanding who qualifies as a friend can be an especially hazy line with social media. An autistic student might say they’re best friends with this person online, but can’t tell you one thing about them as a person aside from their video gaming skills through a shared online activity. This is where a visual with some clearly defined attributes can be a helpful teaching tool in understanding who is a friend and how much you should be sharing with people online.

Sometimes understanding who qualifies as a friend can be an especially hazy line with social media. An autistic student might say they’re best friends with this person online, but can’t tell you one thing about them as a person aside from their video gaming skills through a shared online activity. This is where a visual with some clearly defined attributes can be a helpful teaching tool in understanding who is a friend and how much you should be sharing with people online.

The innermost circle is listed as just the student. The next circle is reserved for family—and then you’d like specific characteristics like how much time you spend with one another and the kinds of things that can be discussed with family members. The characteristics are listed for each circle level as they move farther away from the student in the middle. The distance in the visual helps to represent their level of intimacy and friendship with the student. After family can be close friends, then friends, acquaintances, online-only friends, and strangers. Adding a color-coded element can be helpful to tie this to the rating scale, so students can recognize that an orange or red means they need to adjust the type of things they share and say.

This is a helpful tool for teaching and self-reflection as the autistic student navigates their level of contact with others, and in turn, what conversations should look and sound like at that level to be considered appropriate.

4. Guided Practice: Conversation Cards and Role-Play Opportunities

Sometimes knowing what to say or talk about can be a real challenge, but the nice thing about interacting with someone across a screen is that it’s not as obvious if you have support to help you through the conversation.

Common tools used by a lot of speech pathologists are conversation cards—these can be things to say or ideas on topics to mention when having an interaction. Sometimes it’s hard to generalize the skill to a real-life, in-person interaction, but this could be a good way for autistic students to practice a skill discretely to have some very positive social interactions via technology. Students will, of course, need to continue to practice and role-play conversation skills in person, but this stepping-stone support to aid in digital interactions can be an opportunity to ease into generalization.

Putting It All Together

After implementing some or all of these instructional tools, a big piece is the self-evaluation and self-monitoring component. Sometimes a simple checklist for the autistic person to refer to can help them monitor how they did during an interaction. A sample might look like:

- I texted a friend once and stopped if they didn’t respond.

- The person I talked to fit the criteria for a friend.

- I asked the person questions about themselves.

An important piece of that self-evaluation is to give the individual action steps if they answered “No” to anything on their checklist. For example, should they apologize to an individual? Do they need to stop talking to someone because they are a stranger? Collaborate and make a plan so that the autistic person is on board and can make sense of the situation. Let them know, if they are ever in doubt, to stop further interactions and follow up with a trusted adult to help make sense of the interaction.

Are there any specific challenges you’ve noticed regarding social interactions through technology that you would like assistance with in developing one of these types of supports? Let us know and we’ll be happy to collaborate!

Frankie Kietzman, Ed.S.

Frankie Kietzman is a Sales Development Associate for STAGES Learning with experience teaching as an elementary teacher, self-contained autism teacher for elementary and secondary students, autism specialist and coach for teachers dealing with challenging behaviors. Frankie’s passion for supporting children and adults with autism originates from growing up with her brother who is deaf and has autism. As one of her brother’s legal guardians, she continues to learn about post-graduate opportunities and outcomes for people with autism. Frankie has a Bachelor’s degree from Kansas State University in Elementary Education, a Master’s degree in high and low incidence disabilities from Pittsburg State University and in 2021, completed another Master’s degree in Advanced Leadership in Special Education from Pittsburg State University.