The Persistence of Time: Managing Time on the Spectrum

Time on the Spectrum

Think about time. Does every task take longer if you’re on the autism spectrum, or if you have a child on the spectrum? Does your family have special rules regarding when and how things get done, based on how one particular person experiences the passage of time? Do you find yourself frustrated at the lack of understanding exhibited by neighbors, friends, teachers, sports coaches, and others? These challenges are often experienced by individuals on the spectrum and their families, but you are not alone.

Some years ago, I facilitated a support group on a college campus for students with “learning differences.” These were typically young people with a variety of challenges to academic success. Some of these challenges were with mobility, hearing, and vision; others were diagnosed with learning disorders and with autism. What I heard repeatedly from my group members was that “everything takes longer” and “they don’t understand.” The homework assignments that would take one roommate of a residence hall 30 minutes to complete, might take the student with learning differences 3 hours to complete. The roommate, passing by our student on the way out to socialize, would say, “Wow, you must be really smart, you study so hard.” The suffering desk-bound student was often yearning to have time for making friends and going out to have fun, but it took so much longer to get the work done, that a social life was not possible. Not only was our student frustrated, but he was lonely and exhausted.

Dali's Painting, "The Persistence of Memory"

Their experience was not unlike Salvador Dali’s famous painting, “The Persistence of Memory,” in which a clock appears to be melting off the side of a table, misshapen; another clock melts around a tree branch, and another is draped over an apparent life form. Like Dali’s art, for the student with autism, time is somewhat surreal and takes on a life of its own, distorted, and seemingly outside of the control of our hard-working student.

A quick look at the diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder shows hidden references to time. There are cultural assumptions about how much time it should take a person to respond to social cues or non-verbal gestures. There are likewise expectations about cognitive processing speed; in Western culture, faster always seems to be better. But is it? The medical model forecasts what the best developmental trajectory is, and that is chronologically anchored. Is your child on track (meaning on time)?

What Is "Crip Time"?

For folks with a culturally normative relationship with time, the autistic person’s relationship with time seems contorted, even out of control. But some embrace what Ellen Samuels calls “crip time.” Instead of neuroatypical persons adapting to the dominant culture’s rigid conceptions of time, crip time embraces the reality of the non-normative. Time, as in Dali’s art, is allowed to bend to the needs of the person who thrives with more flexibility. Time adapts to the shape of what is present, what is real.

Samuels talks about the shift in her own disability severity from being a person with a problem, to being a problem. And isn’t this the cultural overlay experienced by autistic persons as they encounter rigid expectations around time, as well as many other cultural norms? They become the problem and not everyone (even loving family members) understands or supports those atypical conceptions of time. The demands of normative time cause even loving family members to demand deference to the clock. Time is lost; can it be found again?

Many of us live in “the sheltered space of normative time,” as Samuels calls the neurotypical experience. We live in it like fish live in water, oblivious to its presence, and unaware that our perception is shaped by the culture. In Daniel Boorstin’s 1983 book, The Discoverers, he discusses the invention of time. Primitive man had no clock, not even a sundial. Keeping track of time is a relatively modern invention. Imagine what forces conspired to make us see time as something linear, to be controlled and managed, or mismanaged, to be saved or lost. Is it an illusion? Could it be different? Is it possible that the neuroatypical brain knows something about time that the rest of us don’t? Like Dali, could we envision time unfolding in a totally different manner? Could we embrace a different conception of time?

Linear Vs. Crip Time

Linear time leads us to assume the normality and predictability of identifiable life stages, such as:

It’s time for our child to start Kindergarten.

It’s time for our child to graduate.

It’s time for our child to go to college.

It’s time for him to choose a career.

It’s time for her to get a job.

It’s time for him to start paying his own bills.

It’s time for her to get married.

What happens when the individual’s inner experience denies these supposedly normal developmental stages? Crip time is non-linear; in fact, putting any non-chaotic descriptor on crip time would be nonsensical. It weaves and flows and starts and stops as the nature of the individual dictates. An old proverb states that “Time waits for no man,” but in fact, sometimes it does, if we allow it, if we make space for challenges to linear time, and if we can conceive of alternative experiences of time as positive, not failures to match a cultural norm.

Samuels speaks of her grief at the loss of time created by her illness, just as my students battled with the time that kept slipping away from them, the time that demanded they stay seated at a desk when they might rather be dancing. What if we were to honor the conception of time that autism presents? More often than not, we see autistic persons as out of sync with normal time, out of alignment with the pace of life in a world that is so ironically subject to the tyranny of time. Time is not immutable; it is what we make of it. Think about time.

We hope you enjoyed the information in this article. STAGES® Learning also offers free downloadable resources to support teaching and learning with individuals with autism. Start with our free Picture Noun Cards and see our collection of other downloadable resources here!

References:

Daniel Boorstin (1983), The Discoverers. Random House: New York.

Ellen Samuels, “Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time.” Disability Studies Quarterly. Vol.37 No. 3 (2017): Summer 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2022 from https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/5824/4684

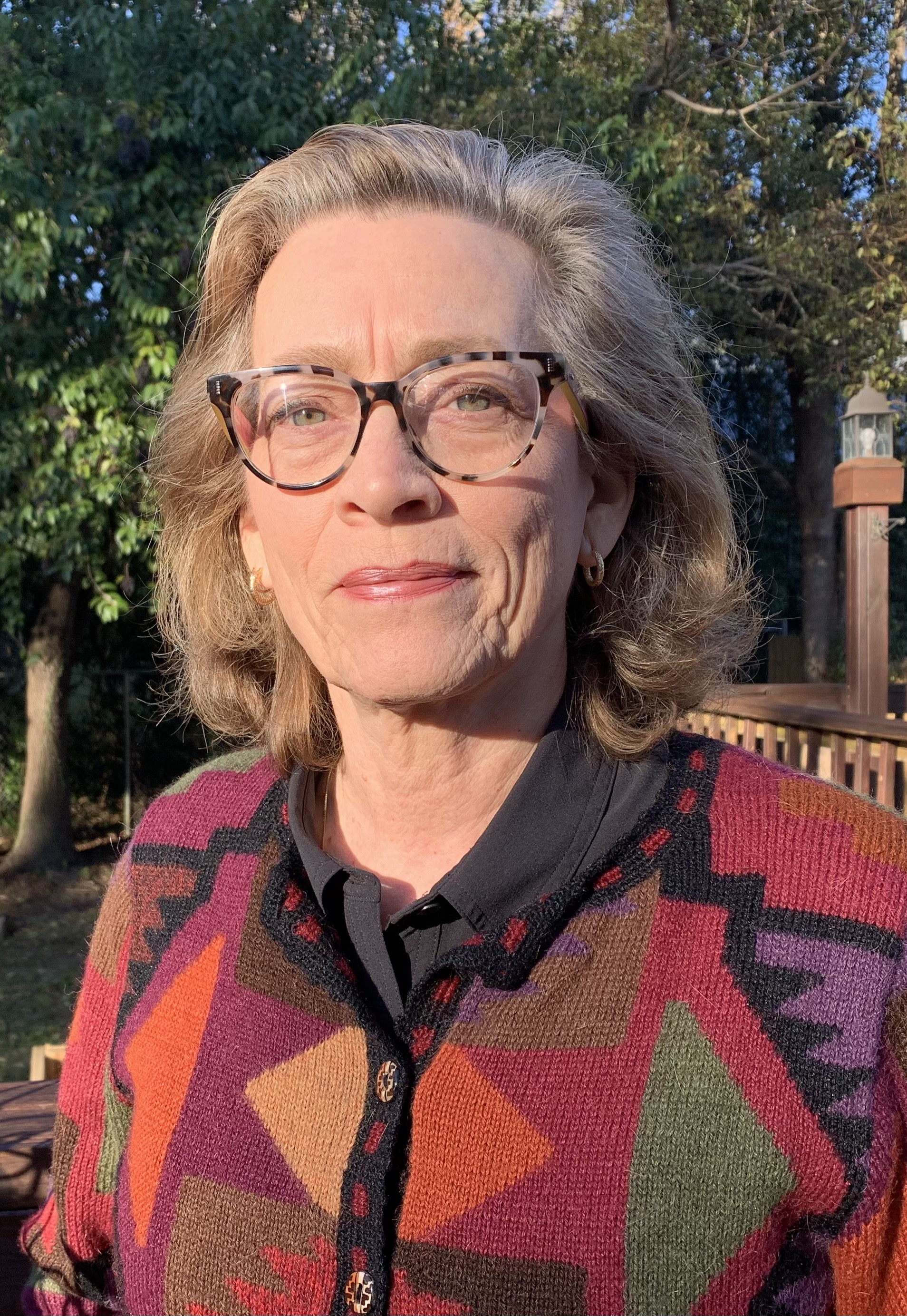

Signe M. Kastberg

Signe M. Kastberg is a licensed mental health counselor with a PhD in Human Development. She taught and directed a Master’s degree program in Mental Health Counseling. She is a psychotherapist, consultant, author, certified in personality typology and is a board-certified clinical sexologist.