Taking the Sting out of Discipline for Autistic Kids

The benefits of setting clear boundaries for autistic children

All children need rules and boundaries to help them know how to act appropriately in different settings and situations, and autistic children are no exception. Rules and boundaries will teach them skills they will need to be successful in life, but how to teach and enforce rules for autistic kids is often a big challenge for their parents and caregivers.

For most of us, the word discipline has a negative connotation and invokes thoughts of giving or receiving punishment. The purpose of discipline, however, is to set healthy boundaries and clear expectations of appropriate behavior, not to punish or embarrass a child.

Traditional discipline techniques aren't always effective for autistic children. Depending on their level of autism, they may not understand the consequences of their behavior and therefore struggle to interpret harsh reprimands. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use any discipline at all. While there are certainly challenges to disciplining an autistic child, setting boundaries instills valuable lessons that will benefit them for the rest of their lives.

Research and Assess

The first step in setting boundaries is to research and assess the child’s capabilities. It is important to remember that each autistic child is unique. A strategy that will work for one child may be counterproductive for another. Some autistic children are developmentally delayed, so the rules should be tailored to their understanding rather than their age and updated accordingly as they grow and progress.

It is also important to remember that certain behaviors, such as stimming, can be something an autistic child uses to self-regulate. Jumping, rocking, or flicking fingers are often calming mechanisms. However, excessive stimming can be disruptive or draw undue attention when out and about. To help in this area, while being aware of the child’s need to stim, try to establish certain times and places for them to engage in stimming activities.

Write Down the Rules

Because autistic children thrive off of sameness, structure, and routine, they need to be taught what the rules are. If you haven’t explicitly told them what the rules are in different situations, you will most likely find yourselves dealing with meltdowns and stress.

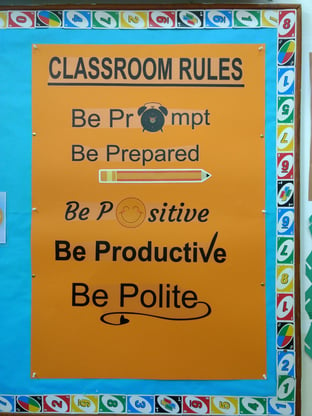

Autistic children typically don’t understand all of the social norms that we easily pick up on. For example, in a restaurant, we know we should be seated for the whole meal. We don’t just get up and walk around the restaurant whenever we feel like it. We use a quiet voice when talking. We don’t shout across the restaurant at a server when we are thirsty. These are the types of rules that need to be written out, preferably illustrated with pictures, so the children know exactly what to expect and how to act. The same thing goes for what is expected from children at school or in the cafeteria.

Autistic children typically don’t understand all of the social norms that we easily pick up on. For example, in a restaurant, we know we should be seated for the whole meal. We don’t just get up and walk around the restaurant whenever we feel like it. We use a quiet voice when talking. We don’t shout across the restaurant at a server when we are thirsty. These are the types of rules that need to be written out, preferably illustrated with pictures, so the children know exactly what to expect and how to act. The same thing goes for what is expected from children at school or in the cafeteria.

Expectations should be broken down visually so the children know what’s happening and what is expected of them. In my book, School Rules Are…?, which I originally wrote for my grandson, I included easy-to-put-together keyring cards of basic school rules for young children.

Start Small

In each setting, visual rules should consist of no more than three to five rules, stated positively. Let the child know what he should be doing, instead of stating what he should not be doing. Place a picture or photograph next to each rule so that the expectation is unmistakably clear.

If possible, and the child is old enough and capable of doing so, involve the child in the rule-making process and draw up the rules together. I recently did this with my grandson, who is now a teenager. We agreed on a behavior contract with specific rewards and consequences, which he signed and dated. He carries a laminated copy of it in his backpack, and his school has a copy of our agreement too. He thrives on clarity and clear rules and leaves for school each morning assuring me he is going to do his very best to have a “good day” and keep the rules.

Once the rules are drawn up, review them often. Talk to the child and show them their rules throughout the day. As your child is adhering to the rules, point or reference the rule that they are following and compliment them specifically for keeping that particular rule.

Be Consistent

It is very important to be consistent when presenting and enforcing the rules. If you have a rule that James needs to do his homework before he can play a computer game, then this rule should be kept every day he has homework. If you promised that James would get a reward for completing his homework, that reward should be given every time he does. If there is a consequence for him not completing it, then the consequence should take place every time he does not complete his work.

Positive Consequences

Rewards for following the rules are very effective. Most young children love to get a special snack, and even teenagers may still appreciate it. When my grandson was little, we used sticker charts a lot. He would receive stickers for following the rules at school throughout the day, and when he filled up his chart, he would receive a previously agreed upon specific reward.

Displaying a reward chart and drawing attention to how well a child is keeping the rules can motivate them to continue with good behavior. It will make them feel accomplished and it encourages self-motivation.

Displaying a reward chart and drawing attention to how well a child is keeping the rules can motivate them to continue with good behavior. It will make them feel accomplished and it encourages self-motivation.

Positive reinforcement should be frequent and occur much more often than negative consequences. Parents often ask me to define the balance between positive and negative consequences when teaching appropriate behavior. A 4:1 ratio is recommended, but don’t hesitate to go above and beyond that.

You can read more on giving positive reinforcement and how effective it is in this article: The Power of Positive Reinforcement in Teaching Autistic Children.

Negative Consequences

Of course, there will be times when a child breaks the rules. It is important to have reasonable consequences in place. When drawing up the consequences, we should remember that the consequences we used to receive as children are not necessarily going to work with our children, especially autistic children. The “when I was young” approach is rarely effective, especially if that approach used to include spanking or harsh rebukes.

Hitting is never okay, nor is yelling or depriving children of their basic needs. Since autistic kids often copy what they see, they may conclude that when someone is mad at them and yells or hits them, that must be the way they are expected to react when they are angry. Yelling or hitting an autistic child can create or increase aggressive behavior and should always be avoided.

Instead, if James did not complete his homework, perhaps he could lose some TV time. Or if the room was not cleaned up after play, a child could lose the privilege of playing with a certain toy until the room is tidy.

Be Gentle

If you feel angry or upset, it is better to wait to administer consequences until you are calm and can discuss the incident rationally with your child.

When administering a negative consequence, it is important to always leave the child with hope of redemption. I never take toys away “forever” by throwing them out. I also do not take away any rewards, such as stickers on the chart they were given previously. That would signal that the task they completed, or the good behavior they worked hard to display, was not worth the effort after all.

There should always be a clear end to the consequence. Carrying a consequence over to the next day or longer is rarely effective with younger children, or with older autistic children who are developmentally delayed. They often won’t remember why they were deprived of a toy or activity the following day, which can create another meltdown or unacceptable behavior, thus creating a vicious cycle of negative consequences. Tomorrow should be a new day and an opportunity to try again and do better.

In conclusion, setting clear boundaries teaches children to do the right thing and to think and act for themselves. It can be difficult to discipline an autistic child, but doing so will teach them the skills they need and prepare them to live a successful and independent life.

Ymkje Wideman-van der Laan

Ymkje Wideman-van der Laan is an author, public speaker, and Certified Autism Resource Specialist from the Netherlands. After working abroad as a teacher and humanitarian for 25 years, she moved to the US in 2006 and assumed the care of her then 6-month-old grandson, Logan. There were signs of autism at an early age, and the diagnosis became official in 2009. She has been his advocate and passionate about promoting autism awareness and acceptance ever since. Logan is the inspiration behind the Autism Is...? (tinyurl.com/5aj73ydd) series of children’s books she initially wrote for him and later published. Ymkje currently lives in California with her now 15-year-old grandson, and besides writing, presents autism training workshops for early childhood educators, parents, and caregivers. You can read more about her story in her newly released book, Autism on a Shoestring Budget, [Early] Intervention Made Easier (https://tinyurl.com/ysxhxbmf). For more information, you can visit www.autism-is.com, www.facebook.com/AutismIs, and/or contact her at autismisbooks@gmail.com.