How to Teach Students With Autism Healthy Habits, Life Skills, and Self-Care

While establishing goals for personal hygiene, healthy habits, and effective self-care skills is important for everyone, individuals on the autism spectrum may need additional support when developing these competencies. Research suggests that teaching self-care skills can help improve: 1&2

- Health and safety

- Self-advocacy skills

- Community participation

- Personal relationships

- Anxiety and depression

- Social communication

- Planning, organization, and resilience

- Executive functioning and career skills

- Personal responsibility and self-confidence

- Life skills, independent living, and career goals

- Self-image, self-esteem, and self-respect

Goal-setting for personal hygiene and self-care skills should begin by completing an assessment of the individual’s existing skill set. This will identify specific areas that need further support, instruction, and reinforcement. Targeting these skills will produce meaningful changes in behavior towards the goals for self-care and personal hygiene being acquired over time.

Strategies for Supporting Self-Care and Personal Hygiene Skills

There are many ways to teach self-care, personal hygiene, and healthy habits to those on the autism spectrum, but approaches should be tailored to fit the unique needs of each individual. The following are strategies that can aid in the development of new self-care skills.

1. Direct instruction

Direct instruction should be provided for those who have not been taught a specific skill before. For example, step-by-step support and explicit instruction should be given the first time a learner does laundry–or another related task–on their own. As personal autonomy and independence on the task is developed over time, support can be withdrawn (i.e., faded out).

Those who oversee the teaching of new skills should always provide sufficient instruction and direct guidance for any skill that has not been previously taught. Practice should continue until the skill is mastered and any remaining competencies necessary for completing the task independently are successfully achieved. Additionally, it is essential to include opportunities for practicing new skills in real-life environments where the task will occur independently–rather than solely within the four walls of a therapy room or treatment center.1

2. Social narratives

Social narratives, (often referred to as Social StoriesTM), are another helpful practice for teaching self-care and personal hygiene skills to individuals on the autism spectrum. These narratives provide visual stories and examples of people who have well-developed self-care skills. Such narratives can be used to educate students who are developing new competencies for healthy habits.

A short social narrative, for instance, may include a person who demonstrates an effective approach to washing their hands at school. Through picture models and written steps, illustrations are given in appropriate detail to depict each portion of the goal leading to task completion. The overarching objective of these stories is to teach healthy self-care skills and competencies for personal hygiene from start to finish.

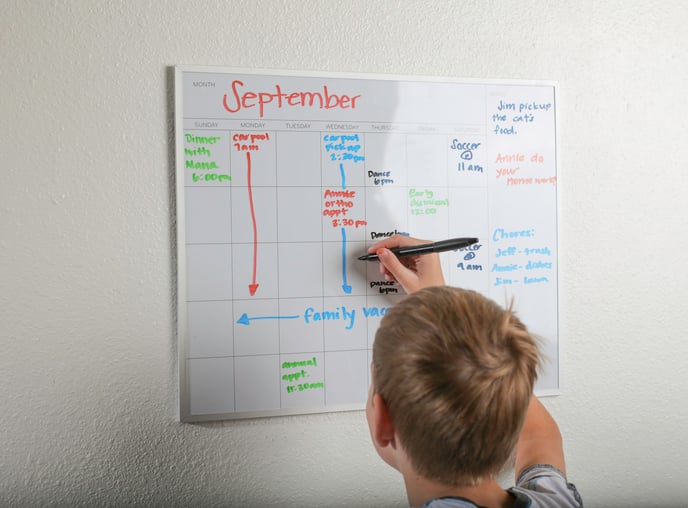

3. Visual schedules, cues, and checklists

Checklists and visual schedules provide prompts, cues, and reminders throughout the day to encourage learners to stay on track with tasks that need to be completed. Because many with autism learn best through pictures and symbols, providing visual cues–along with short, written prompts–on a daily schedule can be beneficial.3

To illustrate, Jennifer, a third-grade student, has a visual schedule of her morning routine printed out and taped on her bathroom mirror. The schedule includes pictures of tasks that must be completed at certain times throughout the morning, and–for each new skill Jennifer is learning–visual prompts are broken down into a simple series of steps to remind her to finish each portion of the task along the way. As each step is completed, it can be taken off the visual schedule or directly checked off Jennifer’s personal checklist.

4. Forward and backward chaining

Forward and backward chaining are two additional approaches that are effective for teaching new life skills to students on the autism spectrum. In forward chaining, a learner is prompted to complete the first step of a new self-care skill (such as tying their shoe), and the rest of the task is completed for them. After the first step is mastered and able to be completed independently by the learner, the student becomes responsible for completing the second step in the chain of tasks for tying their shoes… then the third,… and so on until the task is successfully completed from start to finish on the learner’s own.

Backward chaining is similar to forward chaining; however, instead of having the student do the first step of a new task on their own, they independently complete the final step in the task chain first. In the shoe-tying example, the final task would be pulling the bow tight, and the learner would, then, work backward in the chain until the entire series of steps are completed independently–including the very first step.4

5. Using motivation and reinforcers

Using effective reinforcers is crucial to ensure that a learner is sufficiently motivated to complete self-care tasks on a daily basis. When a child knows how to complete a task but chooses not to, a lack of motivation might be at play–rather than a skill deficit that requires direct instruction.

In the case of insufficient motivation, it is important to provide individualized reinforcers–such as toys, attention, sensory items, or edibles–to encourage the child to participate in the self-care task or activity. Reinforcement should always be delivered immediately after the skill is completed. Remember to make it fun and keep it engaging!

6. The “first then” rule

Implementing the “first then” rule with learners on the autism spectrum can be another effective way to bolster motivation, teach important self-care skills, and improve one’s quality of life and level of independence. This strategy–which is also known as the Premack principle–requires the learner to complete a task that is less enjoyable (i.e., more difficult) before engaging in an activity that is fun, enjoyable, and functions as a reinforcer.

To demonstrate this technique, Sarah’s mom requires her to take a bath and brush her teeth at night before she can watch an episode of Peppa Pig. In this way, Sarah must first complete self-care activities, and then she can watch a show.

7. “High-p” strategies

“High-p” strategies are slightly different from the “first then” principle because an easy task (or behavior that is likely to occur) is completed first. This helps the learner build up to increasingly difficult tasks, activities, and demands. It is essentially the same as the “first then” principle–but in reverse.

An example of a “high-p” strategy in action is having Noah wash his hands before he brushes his teeth. While both of these skills are important for personal hygiene, Noah finds washing his hands more enjoyable than brushing his teeth, so he begins with the task of hand washing before brushing his teeth when getting ready for bed at night.

Similarly, completing a sheet of math problems with easier problems given first is another example of a “high-p” strategy because the student solves simpler problems before more difficult ones.

“High-p” strategies work by capitalizing on a student’s history of task compliance and existing level of motivation. Presenting an easy task before a more challenging one is thought to help the learner get started on an activity, making it easier for difficult tasks to be completed subsequently.5

8. Functional communication

It is necessary to ensure that individuals on the autism spectrum have a strong and functional form of communication that is easily understood by those around them. While the most common form of communication is spoken language, learners with autism may require an alternative system of communication that is tailored to their unique needs.

Sign language, pointing, writing, picture exchange communication systems (PECS), touching, and even eye gazing are all forms of communication that can be used instead of verbal (i.e., spoken) language. Students must be able to efficiently and effectively communicate their needs to make requests, ask for help, and stay safe on a regular basis.

Teaching developmentally appropriate personal safety, leisure, self-care, and hygiene skills to those on the autism spectrum is crucial. Some basic forms of self-care and personal hygiene practices include hand washing, bathing, teeth brushing, and–even tasks we don’t think about as often–like trimming fingernails, getting a haircut, or journaling. Keep in mind that each of these daily living skills may require specific training, and competencies should be adapted to meet the individual needs of the student.

What are some other ways to teach children with autism effective self-care and personal hygiene skills?

References

- https://www.autismspeaks.org/life-skills-and-autism

- https://www.lumierechild.com/lumiere-childrens-therapy/do-it-yourself-using-self-care-skills-to-develop-independence

- https://www.iidc.indiana.edu/irca/articles/teaching-tips-for-children-and-adults-with-autism.html

- https://www.elemy.com/studio/aba-terms/forward-chaining/

- https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/wp-content/uploads/misc_media/fss/pdfs/2018/fss_high_p.pdf

For more information about teaching self-care skills to students on the autism spectrum, check out our free downloadable handout here!

Kenna McEvoy

Kenna has a background working with children on the autism spectrum and enjoys supporting, encouraging, and motivating others to reach their full potential. She holds a bachelor's degree with graduate-level coursework in applied behavior analysis and autism spectrum disorders. During her experience as a direct therapist for children on the autism spectrum, she developed a passion for advocating for the health and well-being of those she serves in the areas of behavior change, parenting, education, and medical/mental health.