While parents and teachers often have nothing but the best of intentions when teaching children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) about safety around strangers, the oft-used moniker “stranger danger” can have some negative repercussions, especially for kids with ASD who tend to be very rigid in their understanding of the world. When parents and teachers talk about “strangers,” they may be envisioning the stereotypically dangerous-looking person characterized on TV and in movies who is lurking around playgrounds and schools in a windowless unmarked van. Adults would understandably want to protect their children or students from someone meeting this description! However, the reality is that this person is just as much a stranger to a young child as the cashier at the grocery store, waiter at a restaurant, or receptionist at a doctor’s office. But if parents teach their children to never talk to strangers, thinking only about the creepy van driver, their child may internalize that they should also not speak to store employees, bus drivers and others. This can be detrimental if a child suddenly finds himself lost in a mall but won’t talk to a security guard trying help him because he’s been taught not to talk to strangers. Strangers in and of themselves are not necessarily dangerous, rather some strangers may be safer or more acceptable for children with autism to speak to than others, and some situations warrant these discussions more than others as well.

While parents and teachers often have nothing but the best of intentions when teaching children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) about safety around strangers, the oft-used moniker “stranger danger” can have some negative repercussions, especially for kids with ASD who tend to be very rigid in their understanding of the world. When parents and teachers talk about “strangers,” they may be envisioning the stereotypically dangerous-looking person characterized on TV and in movies who is lurking around playgrounds and schools in a windowless unmarked van. Adults would understandably want to protect their children or students from someone meeting this description! However, the reality is that this person is just as much a stranger to a young child as the cashier at the grocery store, waiter at a restaurant, or receptionist at a doctor’s office. But if parents teach their children to never talk to strangers, thinking only about the creepy van driver, their child may internalize that they should also not speak to store employees, bus drivers and others. This can be detrimental if a child suddenly finds himself lost in a mall but won’t talk to a security guard trying help him because he’s been taught not to talk to strangers. Strangers in and of themselves are not necessarily dangerous, rather some strangers may be safer or more acceptable for children with autism to speak to than others, and some situations warrant these discussions more than others as well.

“Safe” Strangers

In order to function in society, people must talk to strangers every day. From ordering cheese at the deli, asking a gas station attendant to fill up the tank, dining at a restaurant, to interacting with repairmen, flight attendants, librarians, or crossing guards, people speak to strangers daily. As mentioned above, by telling young kids with ASD that they shouldn’t talk to strangers, teachers and parents are likely doing them a disservice. Not only is it okay for people to talk to strangers, it is indeed an expected life skill that becomes more and more important for all children as they get older and become more independent of their parents. Because children with autism are sometimes very rule-based and compartmentalized, teaching them not to talk to strangers when they are four years old may manifest itself as refusing to order lunch from a cashier at a fast food restaurant when they are fourteen years old because the cashier is a stranger. Rather than insisting that all strangers are dangerous, children should instead be taught how to determine the difference between the creepy van driver on TV and the “safe” or expected strangers that are encountered in every day life.

One way to talk about safe strangers is to describe who a student might expect to see in a given location and what those people look like. For example, we can expect to see cashiers, shelf stockers, and butchers at a grocery store and they each will likely be wearing a uniform with a nametag that clearly identifies them as someone who works in the store. In a restaurant we would expect to see hosts, waitresses, and cooks, again each wearing a uniform and/or nametag that identifies them as an employee of the restaurant. When a child is able to identify the safe or expected strangers in these places, they will be better able to know who to go to for help if needed as well as better be able to anticipate the people who might talk to them in a given environment.

While identifying the different types of unknown or unfamiliar people that children might encounter throughout their day is important, understanding the types of interactions that are expected with these strangers is equally vital. A young child with ASD who identifies the teller as a safe stranger inside the bank should also understand that it is not okay to hug or kiss the teller, and that the teller should also not be hugging or kissing them. The bank teller should only be identified as a person who can help accomplish a task at the bank or help the child if they should become lost. Children with autism can be very trusting and might think that the identified expected stranger or “community helper” can be considered a friend or acquaintance, especially if the same workers are seen time after time at stores frequented by the child’s family. Kids need to understand that this is not the case, even with really friendly familiar strangers, because the child could overgeneralize their relationships with expected strangers to all unknown people. For example, if Frank identifies that Susan, an employee at the local Target, is a very kind stranger and doesn’t mind that Frank holds her hand, Frank may begin to think that it is okay to hold the hand of any Target employee. While this might be cute behavior from a little boy, it certainly will not be looked upon as kindly when Frank is a thirteen year old boy still trying to hold hands with store employees. Similarly, if Frank is used to holding Susan’s hand and one day mistakes another shopper for Susan, he may find himself holding the hand of an unfamiliar potentially unsafe stranger. Or worse, a shopper who has noticed Frank’s affinity for hand-holding may one day decide to take Frank’s hand during the 3 seconds his mother isn’t paying attention, and walk right out of the store with him, with Frank not thinking anything of the situation because he is used to hold hands with strangers in the community.

It is for reasons such as this that children with ASD need to understand not only who they should be interacting with in the community, but also what the expected behaviors are during these interactions.

Visual Representation

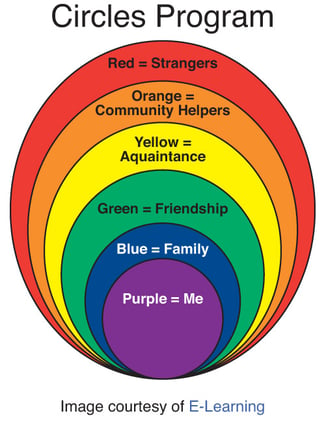

Teaching about safe strangers and expected behaviors with them can be difficult. One visual representation that has been used successfully to teach students with ASD about the different people they encounter in their lives and the expected social boundaries with these people is that of colored, nested, concentric circles. The smallest circle, in the middle of all other circles, represents the individual, in this case a child with autism. The next circle typically represents the child’s family, with the circle around that representing their friends, teachers, or other people they encounter regularly, and finally the largest circle being for strangers. Each circle and its corresponding label and color can then be discussed in terms of who would be in that circle and the kinds of conversation, touch, and behavior that would be appropriate in each.

For example, people in Samantha’s “blue family circle” include Mom, Dad, brother Timothy, Nana, and Uncle Joe. It is okay to hug and kiss people in her blue circle, if she wants to, and tell them she loves them. This might contrast her “orange community helper” circle, in which many of the “safe” strangers she could encounter during the day are found, such as a cashier at the grocery store, a bank teller, and a crossing guard. These could be people whom she sees regularly, but does not know well, and appropriate behavior may be waving, as opposed to hand shaking or hugging, which happen with people in other circles. The largest, outermost circle is often red and labeled as strangers. (This is where the creepy van driver from earlier would be found.)

For example, people in Samantha’s “blue family circle” include Mom, Dad, brother Timothy, Nana, and Uncle Joe. It is okay to hug and kiss people in her blue circle, if she wants to, and tell them she loves them. This might contrast her “orange community helper” circle, in which many of the “safe” strangers she could encounter during the day are found, such as a cashier at the grocery store, a bank teller, and a crossing guard. These could be people whom she sees regularly, but does not know well, and appropriate behavior may be waving, as opposed to hand shaking or hugging, which happen with people in other circles. The largest, outermost circle is often red and labeled as strangers. (This is where the creepy van driver from earlier would be found.)

When teaching about the different circles, the colors can become helpful cues to use in real-life scenarios. For example, if Samantha tries to hug an unfamiliar waiter at a restaurant, her parents could remind her that waiters are in the “orange circle” and cue her to wave rather than hug. As the child (and her family and teachers) become more familiar with the circles, their colors, and the expected behaviors in each, she may only need a verbal cue of “orange circle” or a subtle waving gesture from her parents to remind her of appropriate behavior.

Not only does the circle representation help autistic children to understand how they should act within each circle, it also helps to clarify the behaviors they can expect from others in each circle. For example, Jonathan might know that he is not supposed to kiss his teachers, who are placed in his “yellow acquaintance circle”. But that also means that teachers, and anyone else in his yellow circle, should also not be kissing him.

Gray Areas

As with most things in life, these social boundaries are not always so black and white. The representation of circles does have some gray areas that parents need to help their children understand on an individual basis. For example, doctors might be placed in a child’s yellow acquaintance circle, which may typically be characterized with behavior such as handshakes or waving. However, during a routine physical a doctor may touch a child in ways that are generally only acceptable by people in a blue circle, such as parents and close family members. Parents must talk to their children about the people that meet these different criteria or perhaps create a circle for “adults who are paid to take care of me” that may contain doctors, personal care attendants (PCAs), babysitters, or others who will potentially be touching and speaking with the child in ways that are generally reserved for close family members.

Another gray area can sometimes happen with extended family members. If Jonathan only sees his aunt once or twice a year, he may not want to hug her because he does not know her very well. In this case, the aunt may be placed in his “green friend circle” or “yellow acquaintance circle”, even though she is technically a family member. Children should never be forced to “go hug Aunt Linda” if they are not comfortable with the touch, regardless of what circle that person may be a part of. It is also important to realize that people in one circle could move to a different color circle. For example, if Aunt Linda buys the house next door and she and Jonathan build a great relationship, she may be moved to the “blue family circle”. Social relationships often change and people may transition in and out of various colored circles over time.

Materials

The Circles Curriculum, a published program from the James Stanfield Company, utilizes the circles representation with their well-established materials, but parents and teachers can adapt this idea by creating their own visuals. Doing a Google Image search for “circles curriculum”, “circles curriculum autism”, or “circles strangers” (among others) may give parents or teachers other ideas about how to create materials they can make and individualize with their children. Simply cutting circles out of different colors of construction paper and using pictures of different people to sort into the different circles might be a helpful place to start.

Safety Strategies

Utilizing a visual representation such as nested circles can be helpful when teaching children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders about the expectations surrounding their own behavior and the behavior of other people they encounter in their community. However, it might also be advisable that parents generate a rule that a child must ask a parent, teacher, babysitter, or other trusted adult for permission to speak with or hug/shake hands with/wave to any adult. Another rule might be that it is okay to talk to strangers, just not go anywhere with them. This way Frank is not holding hands with anyone at Target without asking his mom about it first, and he’s certainly not going to leave the store willingly with someone he doesn’t know.

Other Resources:

Teaching children with autism about strangers is an important but challenging task. Below are other resources that parents and teachers may find helpful in thinking about meaningful ways to teach safety skills to their children and students with ASD.

- Adir Levy, Ganit Levy, Mat Sadler (2017). What Should Danny Do? (The Power to Choose Series). Elon Books.

- This article from parents.com is geared toward typically-developing children, but has great suggestions for teaching stranger safety to young kids:

http://www.parents.com/kids/safety/stranger-safety/rules-for-stranger-safety/

- A response to a FAQ from the National Autistic Society about how to help a child with autism to understand that it’s not okay to hug strangers, focusing on the use of social stories and circles visuals to teach:

http://www.autism.org.uk/living-with-autism/understanding-behaviour/behaviour-common-questions-answered/my-son-will-hug-strangers-in-the-street.aspx

- Article from the Center for Autism Research at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia detailing stranger safety, as well as mentioning the additional challenges brought by the Internet and social media, and links to role-playing scenarios for kids:

https://www.carautismroadmap.org/stranger-danger/

![]()